High dropout rate among Orang Asli schoolchildren cause for concern

GUA MUSANG: It was almost noon and the searing heat of the sun could be felt even inside the traditional Orang Asli hut made of bamboo walls and a thatched roof out in the wilderness here.

The area is Pos Simpor, located about 98 kilometres (km) from Gua Musang, it is said to be one of the most remote Orang Asli settlements in Peninsular Malaysia.

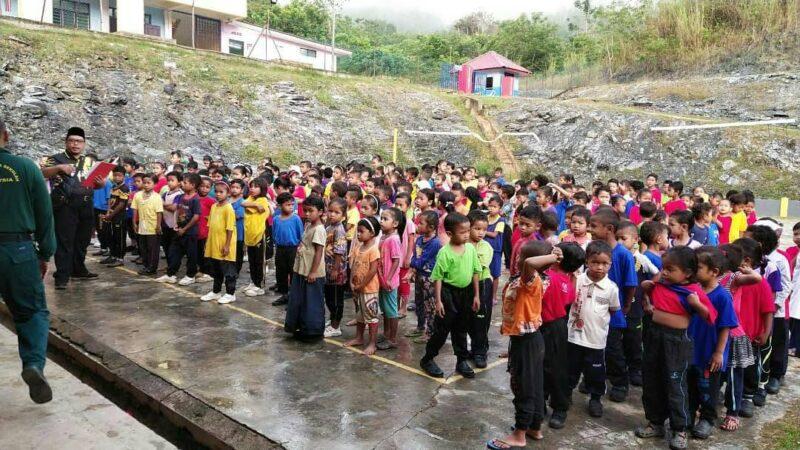

About 30 Orang Asli, mostly men from the Temiar clan, had gathered in the house to talk to the Bernama journalists, touching mainly on their children’s education matters.

They spoke animatedly until a dusky, middle-aged man started to talk.

Ayel Ajib, 55, seemed calm initially but he choked up and tears welled up in his eyes as he recollected the tragedy that impelled him to stop sending his children to school.

He is the father of Ika Ayel, the nine-year-old child who was among seven Orang Asli children aged between seven and 12 years old who ran away from their hostel at Sekolah Kebangsaan (SK) Tohoi, Gua Musang, on Aug 23, 2015, fearing that they would be reprimanded by their teachers for sneaking out for a swim without permission.

After going missing for nearly 50 days in the thick jungles of Pos Tohoi, only two of the children survived the ordeal. The remains of Ika and three others, all from Pos Simpor, were found by a search and rescue team but the remains of the seventh child have never been found.

“It happened eight years ago but the trauma remains till today,” a visibly distraught Ayel told Bernama.

“I received my child’s body (skeletal remains) in a box. It didn’t look like what a body should look like,” he said.

Following the incident, the grieving father-of-five decided to pull his three other children out of school. All three – Reney who was then in Year Five, Jurey (Year Four) and Magroy (Year One) – were also pupils of SK Tohoi.

Ayel also never sent his youngest child Iswan to school. The boy would have been in Form One today had he gone to school when he turned seven.

Like Ayel, many parents in Pos Simpor flatly refused to send their children to school after the tragedy as they believed the school authorities had not been taking care of their children well.

The deficit of trust in the school institution and not-so-cordial relations between the parents and teachers are not restricted to SK Tohoi but also exist in schools located in Orang Asli settlements in other parts of the peninsula.

The rather high dropout rate in SK Tohoi – which at 50km away is the closest school for the Orang Asli children in Pos Simpor – is nothing new as even before the tragedy occurred attendance stood at around 75 to 80 per cent.

The Education Ministry (MoE) and other agencies are trying to persuade parents to send their children to school but have met with little success due to the existence of longstanding issues that have yet to be resolved.

Ayel said he is not against education but hoped the government would build a school closer to their settlement so that their young children need not stay in a hostel.

“Yes, I’m still traumatised by my child’s death. My other children want to go to school as they have many friends there. But please build a school close to our kampung to make it easier for us to send our children to school. Now even children as young as six years old have to stay in a hostel if they are sent to school.”

The Orang Asli children attending SK Tohoi are forced to stay in a hostel because it is not possible to go to and fro the school and Pos Simpor daily as each trip will take around five hours by motorcycle or up to 10 hours in rainy weather.

Pos Simpor, which has a population of over 900, comprises 12 villages, namely Kampung (Kg) Penad, Kg Sedal, Kg Sumbang, Kg Ceranok, Kg Dandut, Kg Jader Lama, Kg Pahoj, Kg Kledang, Kg Pos Simpor, Kg Halak, Kg Rekom and Kg Tihok.

Admitting that the dark episode of 2015 had affected SK Tohoi’s attendance records, Pos Simpor acting headman Mohd Syafiq Dendi Abdullah, 30, told Bernama many parents feared their children will meet the same fate if they were sent to school.

He said the two children who were found alive after going missing for 50 days, Norieen and Miksudiar, who are now 17 and 18 years old respectively, cannot find a job as they do not have any educational qualification.

“They dropped out of school (after the incident). They have no qualifications and are scared to meet outsiders. They are still traumatised as they saw their friends dying in front of their own eyes. According to them, some of the children were eaten by monitor lizards but they (survivors) couldn’t do anything to save them because they were weak from hunger,” said Mohd Syafiq Dendi.

He said teachers from SK Tohoi have, in the meantime, succeeded in persuading some parents to allow their children to resume schooling.

Currently, the Sijil Pelajaran Malaysia or SPM is the highest qualification attained by the children of Pos Simpor villagers who managed to complete their secondary education. Most of them are now working as rubber tappers; those who left their settlements are working as lorry drivers or factory workers.

Bernama observed that many parents here are aware that only education can pull their community out of the clutches of poverty. Some of them regret putting a stop to their children’s schooling as it has prevented them from mastering the three Rs, namely reading, writing and arithmetic.

What’s more, the Covid-19 pandemic and subsequent movement restrictions in 2020 and last year worsened the Orang Asli children’s access to education.

The issue of children dropping out of school due to geographical or socioeconomic reasons is not merely limited to Pos Simpor but also other Orang Asli settlements located in remote parts of the peninsula.

Department of Orang Asli Development (JAKOA) director-general Sapiah Mohd Nor said her department has identified several factors for the fairly high dropout rate among Orang Asli children.

“In general, among the factors that influence the percentage of pupils leaving JAKOA or MoE’s watchful eyes are the school ecosystem itself and the lack of an icon for the pupils, who also lack the support and encouragement of their parents. Other factors include the failure of the Orang Asli to adapt to other races and the attitude of the parents.

“From the geographical perspective, most Orang Asli villages are scattered in remote areas, thus lowering their degree of accessibility to education,” she said in a written reply to questions posed by Bernama.

In October this year, former Rural Development Minister Datuk Seri Mahdzir Khalid reportedly said over 10 per cent of Orang Asli children have dropped out of school due to various factors including logistics and the parents’ negative attitude towards education.

In November last year, MoE was quoted as saying that 42.29 per cent of Orang Asli students did not complete schooling up to Form Five compared to 58.62 per cent the previous year (2020).

The dropout issue was also acknowledged in a report by the Institute for Democracy and Economic Affairs (IDEAS). The October 2020 report, titled ‘Education Policies in Overcoming Barriers Faced by Orang Asli Children: Education for All’, was prepared by researcher Wan Ya Shin.

According to the report, “education gaps continue to persist between Orang Asli children and non-indigenous children till the present day despite continuous efforts and investments over the years.”

It said that based on data on the primary to secondary school dropout rates among Orang Asli and national students (2016 to 2018) from MOE, despite the declining dropout rate among Orang Asli students after Year 6, it was still high in comparison to the national rate which was consistently below four per cent. The Orang Asli students’ dropout rate was above 17 per cent and it increased significantly to 26 per cent in 2017.

At the state level, the issue of school dropouts among Orang Asli students was more prevalent in Kelantan and Terengganu and less in Perak, Kedah and Johor.

In 2018, the dropout rates after Year 6 were highest in Kelantan and Terengganu at 41 per cent, followed by Selangor and Federal Territory (27 per cent), Negeri Sembilan and Melaka (22 per cent), and Pahang (19 per cent).

The three states with the lowest dropout rates were Johor (one per cent), Perak and Kedah (three per cent each).

The IDEAS report said the disparities in the dropout rates “could be due to state-level governance of schools, in which guidance and support provided at state- and district-level varies among the states.

“It could also be due to the different level of involvement of the civil society and NGOs (Non-Governmental Organisations) in supporting the educational programmes at the community level.”

The report’s author Wan, however, said the dropout rates after Year Six did not reflect the actual overall situation because data on children who never attended school or dropped out while in primary school were not included in the statistics.

Meanwhile, Universiti Malaya Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences senior lecturer Dr Rusaslina Idrus said the existing data indicate that the high dropout rates among Orang Asli students are something to be concerned about.

She also expressed her concern over the lack of complete data on the Orang Asli education issue.

“Currently we only have data on those who dropped out of school (after Year Six). They went to school but did not complete their education or dropped out. But our country doesn’t have data on, for instance, (Orang Asli) children aged six or seven who have never been to school,” she said.

Rusaslina, who has conducted various studies on Orang Asli matters including her latest entitled ‘Contextualising Education Policy to Empower Orang Asli Children’ which she did with Wan, said it is important to have such data including identifying the factors hindering them from going to school.

The issue of children not being able to attend school due to the lack of basic facilities is serious because it contravenes the provisions set under Article 26 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and Article 28 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child.

It also goes against the Education Act 1996 which was amended to make it compulsory for all Malaysian children aged between six and 12 to go to school.

In this regard, said Rusaslina, it is important for JAKOA to collect data and information on Orang Asli children who have never attended school. This is to enable MOE to draw up the necessary intervention plans so that no children from indigenous groups are marginalised in terms of education.

“The (2015) incident involving the pupils of SK Tohoi affected their trust in our schools. Based on our research, other (Orang Asli) villages were also impacted with many parents feeling that schools were not safe places.

“Even though many have recovered from that trauma, other issues contributing to children dropping out of school persist. These issues must be looked into considering that education is a basic right of all Malaysian citizens,” she added.

Bernama