Story of the Peace Corps in Malaysia

The arrival of the first Peace Corps volunteer group exactly six decades ago paved the way for a lasting and mutually beneficial relationship between Malaysia and the United States, writes ALAN TEH LEAM SENG

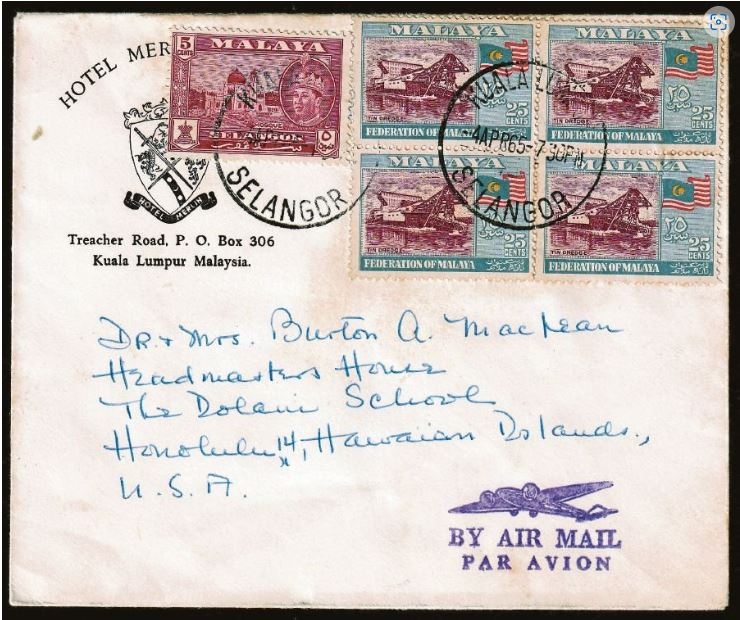

A FELLOW philatelist comes by the house one balmy afternoon, looking as happy as a lark.

Without a word, he jubilantly hands over a stack of letters before sitting back to observe my reaction. Realising that he was putting me to the test, I carefully scrutinise the envelopes and their contents for clues.

Before long, it becomes evident that these letters, dating back to the mid-1960s, were from a Peace Corps (PC) volunteer to his loved ones back home in the United States.

KENNEDY’S CHILDREN

While heaping praise on the spot-on deduction, my friend excitedly empties his knapsack to reveal related items accumulated over the years. Within minutes, the prized memorabilia start weaving a spellbinding story about PC activities in our country, beginning from the day the first 36 volunteers arrived in Kuala Lumpur on Jan 12, 1962.

Turning back the clock even further, he reveals that the PC owed its origin to John Fitzgerald Kennedy, who made its establishment his administration’s first Executive Order after becoming the 35th US President. These volunteers, called “Kennedy’s children”, began making positive impact by successfully transcending cultural and political barriers in Ghana, Nigeria and the Philippines not long after.

Malaya was among the other countries approached just weeks later by Sergeant Shriver, the first Peace Corps Director.

He, like many other Americans, held Tunku Abdul Rahman in high regard, especially after his widely covered visit to Washington D.C in October 1960 to help defuse tensions in West Irian.

Coming across as a pragmatic and progressive leader, the Malayan prime minister also convinced many during his stop-over at the United Nations headquarters in New York that his newly independent country was all for the pursuit of fair and peaceful development through international cooperation.

Tunku welcomed Shriver’s offer, as the presence of skilled and trained volunteers would help spur development and provide assistance to effectively implement national policies.

Although this assistance was provided free to fortunate countries like Malaya, the burden of volunteer sponsorship fell on the US where individual annual cost, including training, living allowance and air passage, as well as administration and overhead expenditures, came up to US$27,000.

Due to the high financial outlay, each applicant had to undergo a rigorous selection process where only one out of five made it to the training stage. Out of those selected, four out of five would make the grade to represent the US for service abroad.

MASTERING BAHASA MELAYU

In order to better prepare them for life in Malaya, prospective volunteers spent two months at the Northern Illinois University where their day started off with breakfast at 7.15am followed by Bahasa Melayu and general Malayan knowledge lessons.

After lunch at noon, further language lessons and physical conditioning were conducted. The last national language class for the day began at 8pm.

Volunteers were also briefed on communist terrorist tactics. Although the 12-year Malayan Emergency had ended in 1960, participants were made aware that bandit remnants still presented threats, especially in the rural Malayan landscape.

Comprising nurses, medical laboratory technicians, architects, road and soil surveyors, secondary science teachers and industrial arts instructors, Malaya’s first PC volunteer group took up assignments at rural and urban areas located throughout the Federation, as well as Sabah and Sarawak.

These participants, who put service before self, sought no material gain but, instead, were after intangible gratifications such as those expressed in a letter mentioning that reward came in the form of satisfaction after witnessing villagers burst out in hearty laughter after a bountiful harvest or parents heaving sighs of relief when their child recovers from a life-threatening bout of malaria.

Although the initial emphasis was mainly on improving health services like medical personnel training and laboratory establishment, focus gradually leaned towards education following an increase in enrolment after the Secondary School Entrance Examination was abolished in 1964, just a year after the Federation of Malaysia was established.

DISTINGUISHED VOLUNTEERS

The Education Ministry heaved a sigh of relief when the sudden teaching staff shortfall was mitigated in part by the timely arrival of five successive Peace Corps Malaysia (PCM) batches.

Making up one of the largest cumulative numbers in the programme’s 21-year history, most of the 436 new volunteers headed to classrooms throughout the country and began mesmerising students with their English, Mathematics, Science and Industrial Arts teaching prowesses.

Their dedication, impressive capabilities and the willingness to serve in the remote areas prompted then education minister Mohamed Khir Johari to urge Malayan teachers to emulate their exemplary attitudes and commendable work ethic.

The Straits Times echoed the education minister’s words when it reported that PC volunteer Barbara Guss won first prize in the national language elocution contest for non-Malay women on July 2, 1964. The Sekolah Tuanku Abdul Rahman mathematics teacher received a silver cup and certificate at the conclusion of the Kinta district finals in Batu Gajah.

Dressed in a red sarong and baju kurung, she won judges over with a speech on the responsibilities of women. When quizzed about her proficiency, Guss attributed her success to the friendly, multiracial Malayan society who conversed with her in Bahasa Melayu as if she was a local.

Like Barbara, other PC members also distinguished themselves in their own field of expertise. Hugh Zimmers and Richard Stahl, both architects, received a gold medal each for meritorious work from the Kedah and Terengganu sultans, respectively. At the same time, Willard Weiss left his mark by personally designing and supervising the US$370,000 Bentong bridge project while attached to the Pahang Public Works Department.

LARGEST PEACE CORPS PROGRAMME

The PCM programme expanded rapidly over the first four years with proportional office and staff size increases to augment personal and professional support for volunteers in the field. While the main headquarters remained at Broadrick Road (now Jalan Raja Laut) in Kuala Lumpur, regional offices were established in Kuantan, Kota Kinabalu, Melaka, Kuching and Penang.

By 1967, the PCM programme was one of the largest in the world with nearly 600 volunteers. While many segments continued receiving invaluable support, it was the health sector that saw the greatest multiplicity of efforts through effective urban and rural outreach programmes. Tuberculosis eradication received the most attention as the disease was then Malaysia’s leading communicable disease.

Some health projects saw PC volunteers acting as catalysts for effective treatments in rural Sabah and Sarawak health clinics, and others provided expertise in therapies for spastic and handicapped children.

Conditions in remote areas were very challenging, with some district dispensaries sited hundreds of kilometres away from the nearest hospital and the only means of communication was either through shortwave radio or days of travelling in small outboard motorboats. Although supplies only arrived once a month, the volunteers gave their best and successfully forged lasting relationships with those they met.

Although most rural PC development projects during those early years were confined to Sabah and Sarawak, the strong rapport enjoyed between the volunteers and locals did not go unnoticed by those on the other side of the South China Sea. Kedah was among the first to put up a request for volunteers to serve as community development workers in rural villages. Their primary tasks of encouraging local initiatives, training village leaders and improving communications between state agencies and village heads were so successful that the pilot programme was expanded to neighbouring Perlis within a year.

MALAYSIA FORGES AHEAD

While highlighting fact that it had been exactly six decades ago to this year that the PC Volunteer programme first took root in our country, my friend showcases several poignant photographs taken in the years leading up to 1970 that showed trained locals taking over the reins as success from the First Malaysia Plan (1966-1970) brought about marked progress and manpower self-sufficiency.

Further strides were seen under the Second Malaysia Plan (1971-1975) as more institutes of higher learning were established to complement the role of University Malaya in providing places for knowledge and skill acquisition to the sizeable first batch of school leavers who entered secondary school in large numbers following the 1964 Secondary School Entrance Examination abolishment.

Together with Universiti Sains Malaysia (1969), Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (1970) and Universiti Pertanian Malaysia (1973), various training institutes were established under the auspices of Majlis Amanah Rakyat to ensure sustained human resource development for continued growth.

The 1970s saw many significant turnarounds in the PCM programme as demand for quality began outstripping quantity.

The priority shift to more experienced personnel coincided with changes in pre-service training. While all volunteers were trained in the US during the early years of the programme, global PC perspectives began changing after it was felt that participants would be better off if they received guidance in the host country. Participating countries welcomed this move with open arms as the geographic training transfer presented the golden opportunity for them to actively participate in the PC volunteer programme planning and imp-lementation.

In Malaysia, training facilities were established at Sarawak’s Tarat Agricultural Centre while other induction centres were prepared throughout the country. Volunteers appreciated these arrangements as the added experience of living with local foster families improved their understanding of the local culture and created lasting friendship bonds.

PCM celebrated its 15th anniversary in 1977 by honouring accomplishments that contributed to Malaysia’s tremendous growth over such a short period of time. Volunteers were lauded for their flexibility and readiness which helped expedited project and programme implementations, and boosted Malaysia’s management sophistication and technological expertise.

At the same time, PC established a worldwide priority programme to concentrate on basic human needs, primarily in agricultural and health projects that would improve and increase sanitation, water quality, food production and nutrition. This new strategy was in line with the Third Malaysia Plan (1976-1980) aspiration of reducing and eliminating poverty.

END OF AN ERA

At the dawn of the next decade, threat of a potential PC budget reduction sparked an irreversible trend that eventually led to the dissolution of the programme. Given the fact that Malaysia stood out among almost all in Southeast Asia as a sophisticated nation with ample natural resources and years of consistent economic growth, the decision was made that no further requests for volunteers could be accepted from 1981 onwards.

Even though the feared PC budget cuts did not come to pass, discussions with the Malaysian government led to an agreed position to gradually phase out the programme due to difficulties faced in recruiting highly specialised personnel to suit specific single input programmes.

After serving in this country for 21 years, the PCM programme finally came to an end in November 1983. Although the farewell was met with much regret, many saw it as a new beginning for the enduring friendship between Malaysia and the US.

After all, the programme was never meant to go on forever and the fact that the Malaysia had progressed to such a point that requested volunteers could no longer fulfil the necessary requirements was already considered a resounding success that made all Malaysians proud.

This year, on the 60th PCM

programme anniversary, a poignant footnote in one of the letters in my friend’s collection rings true for the nearly 3,500 volunteers who once called Malaysia their home away from home: “Although I leave today with the heaviest of hearts, the warm smiles seen and the affectionate embraces received will make my determination to return and renew ties with those in this blessed land burn even deeper.”

NST